Rhoda Green's Blog

It is Written

Author’s comment: Every year on Rosh Hashonah and Yom Kippur I am once again moved by the prayer-poem (piyyut) known as Unitaneh Tokef. It begins: On Rosh Hashonah it is written, on Yom Kippur it is sealed . . . and goes on: who shall live and who shall die . . . However, the lines that speak most personally and profoundly to me are those that read: (It is written) who shall be secure and who shall be driven; who shall be tranquil and who shall be troubled . . . We may constrain our more destructive urges and nurture our positive impulses, but in the end, we are who we are, some of us secure, some driven, some tranquil and some troubled. The Unitaneh Tokef, with its rich understanding of, and compassion for, the human condition has informed my poem and given it its title, It is Written.

Rhoda Rabinowitz Green

It is Written

Who shall be tranquil . . . who shall be troubled . . .

“Your mother went peaceably in the night,”

I heard her say over the phone.

How’s that?

Neither living nor leaving was ever serene

my quiet caller surely must mean:

to everything there is a season.

“You’ll want to view her remains,” she presumed.

I don’t know, why would I?

Why would anyone?

She is after all, dead

and the dead don’t care who is there.

3 a.m. my body aches

to rest

sleep.

When the sun has risen;

after brushing teeth and hair,

after coffee

will be time enough.

In darkened room I see she’s gone where I can’t follow.

Died from fright, at least it seems,

stunned into silence

dumbed mid-thought

freeze-framed

Polaroid.

Eyelids shuttered,

slitted gaze devoid of sight

stares down at

nothing

Her mouth an open silent scream

black saliva caught midstream:

congealed threads string parted lips.

Jaundiced, her skin lies stretched

deprived of movement

deprived of breath

botoxed

Before death shocked she lay comatose

body frail, legs and feet small intrusions

beneath the sheet.

Trembling hands rattled padded rail

tore at gown and chest, then came to rest

but not for long.

Arms floated, hovered there

spread-winged seraph soared through air,

gliding downward

up again, again again

searching for a calmer realm.

A rolled towel supports her neck

I suppose to keep the head in place

a blessing, should I unwittingly disturb the space

as fingers stroke her hardened hair —

matted, stiff, the scalp shows through;

caress her brow, then draw back

bewildered.

Indifferent, ungiving touch.

Stone angel

She died at last

organs intact, heart still strong

consequence of her life-long habit of walking;

walking the malls —

alone

she used to say.

She died, at last.

No food, no water

starvation and thirst

her choice

nothing in, nothing out.

Sweet cloying smell of death

replaced with talc

yellow pallor, disguised with powder:

instant health achieved with cosmetic.

They’ve given her a prostitute’s blush

slashed her eyebrows angry-brown

rouged her lips harsh blood-red

This is what happens once you’re dead.

Someone’s coiffed her head of white

curled it, fluffed it, sprayed it, splayed it

against the satin; plumped her cheeks —

How? With cotton?

Porcelain painted doll.

No sign of life

None of the struggle

preserved.

There was one sign:

purple-black bruises tattooing her arms

exposed by the short-sleeved dress she had on.

One that I chose.

What was I thinking?

They said:

“Bring her clothes like she’s dressed for a party.”

Brazen denial

Grand illusion

I do not know this manikin.

* “It is Written” was first published in Parchment, 15th Issue, 2006-2008

MOST RECENT POST, FEBRUARY 2019

UBER BOB, II

On Monday, February 11, 2019, at 1 a.m., Bob left us. But for the very last agonizing throes of dying, he was to the end Uber Bob, smiling, good-natured, uncomplaining.

What bitter irony. How distressing, to watch a humanities literature professor robbed by aphasia, consequence of a stroke. Robbed of that around which his life had revolved: words and the understanding, appreciation, communication and expression of ideas. Especially painful for his wife, Rheba, losing bits of him day by day. Losing those conversations that forever more could only be imagined, daily thoughts and feelings, no matter how inconsequential, that are the very stuff of intimacy. To what degree Bob was aware of his loss, how frustrated by his inability to express his thinking, we’ll never know. Were words locked in somewhere, just beyond his reach, like a word we know but can’t access, can’t pull forward? Or were the words no longer there at all, gone from the subconscious memory? What then was he thinking? Communication of love must subsequently come through the language of eye and facial cues, and touch. Rheba gave him an abundance of that, hugging, stroking, kisses that brushed his cheeks and forehead.

Ever optimistic she provided the stimulation of concerts, plays (yes, plays), movies, dining out, classes for memory recall, exercise . . . Bob, ever willing. His expression ever bright. His love of music, listening to his CDs, sustained him: music, that which speaks directly to the heart and soul.

He loved his family, but adored his wife, Rheber (sic), and never stopped talking of her with obvious, beaming, pride. When I, Rhoda, would phone, asking to speak to Rheba, Bob, in Boston-speak would shout to her, “Rheber, It’s Rhoder! Forever and ever, we became Rheber and Rhoder. This is a Robert-ism I will never forget, affectionate monickers I’ll never stop using.

I won’t go into Bob’s physical and cognitive state as it devolved because I want to remember him for those qualities that defined his being. He was not one for small-talk. Had no trouble finding his voice if the topic were works of literature, authors, ideas, any of the arts and humanities, politics. Usually those conversations happened one-on-one. He was one of the best teachers I have had, in academia perhaps the best. At the beginning of each class, he’d briefly review the material of the previous week, similar to replays of short beats from a previous episode in a TV series. One would assume this practice to be an obviously meritorious pedagogical technique. Perhaps it is in fact used by other profs or lecturers, yet it is not one I’d observed in previously attended university classrooms. Learning in Bob’s classes, then, was cumulative. No one who had faithfully attended them would need to cram for the final exam — cramming, that which results in forgetting the day after everything memorized the night before.

Bob’s enthusiasm for his subject was infectious. Having audited his York University course on Love as a theme found in literature from the Greeks to the present day, I watched and listened as he “took centre stage” in front of his class, at once displaying the often surprising inner core, command of material and ideas, the charismatic presence and impeccable timing of a first-rate stand-up comic, the best of whom are coming from a place of deeply-felt gravitas.

While many others were pursuing titles and promotions, Bob always claimed to be just “tending my gahden (sic).” That’s Boston-speak for planting the seeds of knowledge.

Bob, you will be remembered, always, as Uber Bob.

Rhoda Rabinowitz-Green

February 2019

On Writing Q&A From Goodread.

What’s the best thing about being a writer?

I don’t know that there is only one best thing. For me, there are many best things. Writing is both intellectually and emotionally creative and challenging. While working, the writer is completely focussed on the present while working out the past. It allows the writer to work through thoughts, ideas, personal and social attitudes and relationships. In researching material for a story or book’s content, a limitless world of learning opens and broadens our understanding of every aspect of life and living. It allows for communication of our most privately held beliefs and emotions. It connects us to our selves and the world outside our selves. And it is a fascinating insight into the proess of language and thought.

How do you get inspired to write?

I needed to fill a creative gap when some health challenges forced me to give up playing; I was a classical pianist. But I don’t wait for inspiration to write. I write on-going whether feeling “inspired” or not. Though pleasurable, writing is work and takes constant “practice,” much like playing an instrument, if you want to do it well.

What are you currently working on?

I have recently finished getting my book, Aspects of Nature, ready for a May 25 launch with Inanna Publications. Also, working on a new story about a woman Holocaust survivor who has built a life around herself of fantasy.

What’s your advice for aspiring writers?

Read a lot. Analyse what you read. Write a lot. Analyse what you write. Edit a lot. Edit from the reader’s perspective.

Ryerson Radio interview with Rhoda

Rhoda’s interview about newly-launched (May 25, 2016) story collection, Aspects of Nature (Inanna Publications) on Ryerson Radio CJRU, The Scope, with Station Manager Jacky Tuinstra Harrison. Have a listen: interview and excerpt from the story that gave the book its title.

Rhoda on CJRU Radio

AND THERE WAS MORNING, AND THERE WAS EVENING; ANOTHER YEAR

Toward Dusk Sunset

I am not well versed in poetry (pun intended), but I do know when a poem sings to me. T.S. Eliot’s The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock is one. I read it long ago for a university Survey of Literature class, but it is only now that I can begin to know it in the sense of deep knowing. Only now can I begin to walk the beach with Prufrock and murmur along with him, I grow old . . . I grow old . . . I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled. Not that I have yet reached that moment of such resigned despair. Still, who among us, approaching the bottom of the inning (60-65) of what is now considered middle age, or gone past, does not immediately and viscerally understand the dark insinuation beyond the literal image; hear the dread in its whisper; the tread of the eternal Footman; or, looking back over a lifetime, comprehend without further explanation, Prufrock’s bewildered: That is not what I meant at all. That is not it at all.

The genius of this poem is that it captures so visually what are abstractions: longing, aging and despair; loneliness, futility and faint-heartedness; inevitability, unrequited love, world-weariness; melancholy; fear. And yes, even impotence. But it is Time, which, like mercury, slidders through our fingers; Time, which is relative; which our own poor consciousness must measure by the clock, never noticing it slide by — as Prufrock (or Eliot) does, standing outside himself, the spectator — the yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window panes; slips by in a minute of a hundred indecisions . . . decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

Were I forced in the middle of the night at the point of a gun to choose the lines that reverberate, pour moi, most profoundly, they would be: (For I) have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons, I have measured out my life with coffee spoons.

So simple. So chilling.

Rhoda Rabinowitz Green

July 2015

Puccini’s Madme Butterfly; Minghella’s Production

Madame Butterfly

Splendid! . . . Words don’t even come close to sufficiently describing the performance I saw/heard on Saturday of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly at HD Opera at the Movies. Anthony Minghella’s production comes as close to perfection as one will ever reach in the arts – perhaps in any endeavour.

The singing was superb, but I’ll mention in particular Kristine Opolais’s Cho-Cho-San (Butterfly). The wedding of her superb voice, its range, richness and control, with the intensity and “truthiness” of her acting, wrapped in a surround-sound of Puccini’s heart-rending score, left nary a dry eye in the house. Patricia Racette, who sang the role of Butterfly in the Canadian Opera Company’s 2014 production, has said, “By the end I literally feel almost turned inside out,”echoing my own feeling as an audience listener, that of feeling utterly destroyed.

But it wasn’t only the music and acting drama that made this opera a cornucopia of sensual ripeness. Costumes, sets, choreography, lighting, offered a visual feast. All came together, integrated such as every composer hopes to achieve, (as Wagner dreams of achieving – my opinion), when at the opera’s climax, Cho-Cho-San must face the truth that the faithless US Navy Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton will not return to her, but in fact has come to take her son away for a better life in America with him and his American wife. Elizabeth DeSchong, who played Butterfly’s devoted servant Suzuki in the 2011 COC production, has said, “It is [just] another woman cleaning up a man’s mess.”

Having nothing left to live for, Butterfly commits hara-kiri: “Who cannot live with honor must die with honor.” At that moment, Butterfly’s red sash is set free, flowing outward in a stream, which, by the enchantment of lighting, becomes a river of blood.

Madame Butterfly; A River of Blood

Perhaps the most astonishing in the Minghella production is his use of a puppet to play the role of Cho-Cho-San and Pinkerton’s son. Usually played by a real child, the role in this production is portrayed by a puppet, manipulated by three puppeteers who stand behind, cloaked in black and who fade from our vision; the articulation of this wooden puppet, its face, neck, chest, arms and hands, legs and feet, transformed as eerily human. With a baldish head and sculpted features, its impassive porcelain face seemed magically to convey sorrow, empathy, sadness, joy, fear, love, in a way that no child actor can.

Can we imagine such a breath-taking moment as when Butterfly blindfolds her son — a puppet!— and sends him off-side:

The pathos of the blindfolded puppet-boy prior to his mother’s suicide, taking faltering steps, is overwhelming.”

Barry Millington, Evening Standard, 7 Nov 05

A puppet was also used briefly to stand in for Cho-Cho-San:

“When, during the “dream ballet” … the puppet representing Butterfly clutches with desperation at the departing Pinkerton, we heard an audible gasp go up around us.”

The Londonist 8 Nov 05

I don’t pretend to be exceptionally knowledgeable on the subject ofstyle; I am learning more all the time. But because of the recent research I’ve done for a series for Inanna’s blog, examining the life and writing of Canadian author Helen Weinzweig, I’ve become increasingly more aware of the use of elements of magic realism where I’m not expecting them. I couldn’t help but be struck by the blend of realism and magic in Minghella’s Madame Butterfly. Despite the music’s high romanticism, its exoticism, Puccini is nevertheless described as “one of the greatest exponents of operatic realism” (Encyclopedia Britannica). True, the realism in the last decades of the 19th century is not the realism of novels and dramas of the same era. We are not so interested in the hard truth of life or its portrayal, but in the opera’s soaring melodies.

And obviously, “magic realism” was not within the vocabulary of Puccini (1858-1924); Butterfly first appeared in 1904. Neither was the idea of using puppets to play a character. Nor do we know if the contemporary Minghella was thinking in those terms when he brought in Britain’s puppeteer troupe, Blind Summit.

However, [bear with me a moment], in Madame Butterfly, the setting is realistic enough; we’re anchored in a known country and familiar cultures, (Japan, America), in a Japanese home, (sliding screens), tea ceremonies, historically correct surrounding events, and all-too-human relationships. In Minghella’s production, integrated seamlessly with that world, with no particular acknowledgment of anything strange, is a wooden puppet with whom characters interact in the most realistically human ways. We accept it unquestionably as possible, if not probable.

Minghella may not consciously have been seeking out magic realism as a style for his production. There are many creative and even practical impulses at work in such an endeavor. But in so effectively fusing what is real and what is magical, there is no doubt that he is very much an artist of his time.

Reality and Entertainment; New Thoughts & a Re-Post

January 2016: I watched a beautiful movie last night on Netflix, “The Second Best Marigold Hotel,” with Maggie Smith, Judi Dench, and that marvelous young actor Dev Patel, who manages by the en of the film to transist from a naive, somewht bungling, over-the-top adolescent-man into a lithe, sexy, confident, even noticeably taller young man. This movie was as delightful, perhaps even more so, that its precedent “The Best Marigold Hotel,”which played back in 2013. When it first opened, back in 2013, I wrote in a blog that the latter, (along with the movie “The Last Quartet”) was “uplifting, without shying away from confronting the prospect of our declining powers.” I can say the same for its sequel: uplifting, joyful, a beautiful portrayal of aging, with its mellowed awareness of time, loss, dreams unfilled, an intense desire to live one’s remaining life to its fullest, and a willingness — a need even — to take risks for personal fulfillment that one is often afraid to take in youth. If you wish to read the 2013 blog on the first Marigold film, please read below:

Best Exotic Hotel Marigold

Post for January 28, 2013:

January 2013: I have seen some wonderful movies lately, two being The Best Exotic Hotel Marigold and The Late Quartet. Quartet was enjoyable and fun, though there were a few things in the writing I could quibble with. Friends have recommended Amour, which I have not seen. What they all have in common is the theme of aging and its challenges. I do not intend to see Amour. The first three are uplifting, without shying away from confronting the prospect of our declining powers. Although I’m told that Amour is a beautiful love story, it is a much more unforgiving look at what we are likely to face, either ourselves personally or those we love, unless we are lucky enough to go in our sleep. Having been through my mother’s tormented journey after my father’s death and her cognitive decline, and with my being all too keenly aware of what lies ahead, I will take a pass on seeing Amour. With the population aging, there seem to be more and more movies dealing with the topic. I do relate to Woody Allen’s famous line: I don’t mind dying; I just don’t want to be there when it happens. And I like my movies to confront the subject with the same lightness of being.

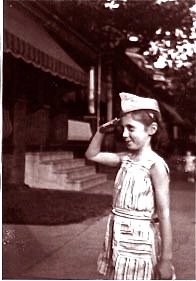

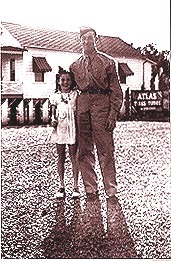

Younger Than Springtime, Older Than Dirt?

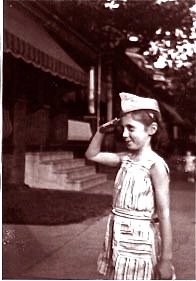

Milton Zahn, WWII

Rhoda Saluting Milt

Some days I feel younger than Springtime and others, as my high school friend Iris Birrer Levy has described, older than dirt. The change from one to the other can happen overnight. Or in the space of a day, as happened yesterday, a Sunday. My 93-year-old Uncle Milt was buried (he died two days before) and my beautiful soon-to-turn-18 granddaughter Stephanie and her beautiful friend Taylor, bought dresses for their high school prom. They stayed with my husband and me for the weekend in order to shop in Toronto (they live in Newmarket, outside of the city.) Late that Sunday, they returned to the apartment and with much excitement, showed us their purchases. I don’t know which event, my uncle’s passing, or the girls, flushed with youthful energy, showing off their new dresses, made me more aware of my age, but I do know which made me feel great, even though vicariously. With their tiny waists, flat tummies and slender hips, the girls were radiant in sleek black strapless gowns (my grand-daughter’s had a long slit the length of her leg), They giggled and allowed me to fuss over them as they posed for cell-phone pics. Gradually, of course, but seemingly overnight, my little Stephanie had become a sophisticated young woman, confident (and sexy), with a smile that lights up my heart and a temperament as pleasing as her outward beauty. It is such a joy to be part of her life.

My uncle’s passing, brought more sobering thoughts. He was my mother’s brother, one of ten siblings. Of the ten, one 91-year-old aunt remains. She is still bright, but is noticeably failing. When she goes that family era goes with her.

Being the first-born, the eldest, of my many 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th generation cousins, I will move into the position of being simply, the eldest. As the generations of cousins grow more and more distant from those who carried the family’s history and traditions, as less and less is orally passed down, much, if not all, of that past stands to disappear or become significantly diluted.

Over the years, I have collected pictures and information on our ancestry, history, traditions and stories that have become part of family mythology. There is a strange existential feeling (I use that word, never totally understanding its meaning, but it feels applicable here) to the awareness that the reality of my growing up is not the reality of the younger family members. The perception I have of my grandparents, aunts and uncles, my memories of them when they were still youthful and, to some extent, of their social era, cannot be the same. This is not a new thought and may even sound trite. It is true of every passing of years. The Second World War of my experience, the Sixties, the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, of Martin Luther King, the horrors of the Holocaust and of the Vietnam War, are dead history to those too young to have experienced them. Still, the awareness of this phenomenon never ceases to amaze me. It is this mystery of the process of life and where we stand in it, this same keen awareness, that my uncle’s passing has engendered in me today.

What will I feel tomorrow? Younger than Springtime or older than dirt?

I’m going to spend as much time with my granddaughter and her friends as she will allow!

Have a Great Day

On the same topic of aging: I recently had another birthday. Let’s just say that I am old enough to remember when as kids we got a quarter for an allowance, which was considered liberal, and when a pair of nylons for young girls and women came in a set of two with a seam down the backs. But today I go to strenuous fitness classes regularly and intensive world dance classes (the vocabulary from Africa, the Middle East and South America); I dress well, am active, travel, have a large circle of friends and a rich family life; engage in an interesting intellectual (that includes computer literacy) and cultural life, and take an active interest in politics; I have had careers in music, teaching and writing. My husband has a similar lifestyle. Neither of us is ready to say goodbye to this world yet.

Now one day my husband and I were crossing a wide street in downtown Toronto. We had parked our car directly across from our destination address and admittedly were jay walking in the middle of the block to get there. The only traffic coming was one car and a bicyclist, both from a comfortable distance away and coming from the same direction. We were only a few steps away from reaching the curb when the car began getting close enough to pass us, with the cyclist not far behind. As the cyclist sped past, the man on the bike shouted out, “F*&#%@’ old people!”

Have a great day.

ÜBER BOB

A Joyful Poet of Words

I have come to call my friend of some forty-five years, Über Bob. Bob was an academic, or as I, tongue-in-cheek, like to call such profs: university “perfessors” (sic). Recently, Bob, now in his late seventies, had a stroke, which left him physically unscathed, but with loss of memory and the ability to access and understand words. This condition is referred to as aphasia.

It has led to some very challenging conversations. His speech is often unintelligible, although it gets better when he is encouraged to take a deep breath and slow his thought processes and speech. But many words he has either forgotten, or can’t produce; hard to tell. As well, the stroke has negatively affected his ability to understand what he is reading.

He makes a mighty effort to overcome these challenges. Bob was a Humanities prof, his area being Literature, so you can imagine what this loss of memory, word recognition and production must mean to him. When asked by his rehab nurse what he did for a living, he responded — amazingly, given his verbal challenges — “I was a poet of words.”

Mahler is Heaven!

Bob happily goes along with his wife and close friends to theatre, movies, concerts. Although his specialty was in the field of early American novelists and poets, and although his knowledge spanned the Greeks to the present day, his great love is music. Orchestral, chamber, vocal, opera. Since his retirement, he spends hours and hours listening to his beloved CDs.

I have never known Bob to be “down;” depressed; grumpy; negative. Absent-minded, perhaps. In his own world. Laissez-faire. Withdrawn in a dreamy or removed kind of way. In the classroom, however, he was “on.” Articulate, witty, thorough, involved. The classroom role brought out the actor, the showman, in him. He seemed to love the spotlight and attention. He earned the students’ affection and regard.

But here’s why I have come to call him Über Bob: I have never seen a stroke victim as (apparently) happy as Bob. If he isn’t, he is putting on a helluva good act. His expression is upbeat, bright with optimism, and his smile, broad. Characteristically, he looks as if he is in a state of surprise, or wonder. Much to our own wonderment, he is more involved and talks, talks, talks, more than he ever did when he was a “poet of words!”

In the early weeks of his stroke, my husband and I, along with Bob’s wife and another close friend, took him to an Italian bakery for coffee and a treat. On entering, Bob uttered, “This is so much fun! I feel such joy! This stroke,” he explained, when he saw our disbelief. “I’m learning so much,” he went on, referring to all the “new” vocabulary he was learning as we filled in what he needed. He expressed delight at all the activity, the “interesting people” (the bakery was crowded and bustling), and the variety of colourful sweets.

The prognosis is that Bob’s recovery of memory and speech will be long and slow; if ever. It is hard on his wife, who, regardless of his good humour, has lost that part of the partner with whom she had shared memories, words and thoughts for over fifty years. Herself an optimistic trooper, I know she will not waver in her efforts to keep Bob stimulated by surrounding him with good company and conversation; taking him on long walks and to all things cultural. And I know he will keep up the struggle.

May he always be filled with joy, humour and a love for learning. He leaves us with a question: Who’s to say what constitutes happiness?

Here’s to Über Bob.

What’s in a Name?

A Rose by any other Name?

What’s In a Name? A rose by any other name does not smell as sweet, contrary to Shakespeare’s Juliet speaking of her love Romeo. What matters Juliette declares, is who one is; or what things are, not their names: O [Romeo], be some other name!

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

by any other name would smell as sweet.

Perhaps not.

This blog is actually a story about three children in one of the lower income districts in Toronto. They are at the heart of this story. But first, I digress to explore the question, What’s in a Name? before coming back to the three children.

Belief that our names are unique dates back to ancient cultures, such as the Egyptian and Judaic, to name just two. According to the Egyptians the name given to a child was as much a part of that child as his or her soul. Ancient cultures also believed that not only names contained intrinsic powerful symbolism, but so did individual letters within them.The 12th century mystical tradition of the Jewish people, the Kabbalah, taught that God created the universe from the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, similar to the manner in which the Egyptian god Ptah brought that which he named into existence. With 22 fundamental Hebrew letters, God formed with them everything to be formed.

Each letter contained the possibility of ascent from an individual life to the larger universe and to the divine. In Reincarnation; Wheels of a Soul, Rabbi Berg tells us: “So powerful is the influence of a name and the negativity surrounding the wrong name, that a Kabbalistic answer for great physical or spiritual illness frequently is a name change. “. . . virtually every case of conflict within an individual personality can be traced to an improperly assigned name.” (!!!)

Now we return to the three children I referred to at the opening of this blog. I met these children while working with a group in an out-of-school-time program designed to provide enrichment opportunities to those children whose parents could not do so. I’ll refrain from giving descriptions (though it kills my writer’s heart), one sister, two brothers, for reasons of privacy. Suffice it to say that they all had the same amiable, even sweet, open expression.

When my colleague presented the girl to me, she said, “Mrs. Green, I’d like you to meet Gentility. And this is “Triumph.” (the oldest brother). The younger: “Resolve.”

Obviously fond of the children, with each introduction my colleague glanced at me, evidently to check out my reaction. What might I think about giving children such names to carry with them through life?

But can any of us doubt the powerful symbolism of their given names? Fail to understand this mother’s hopes for her children? The paths she wished them to follow and live up to?

I had only just met them, so had no way of knowing if they were living up to their names thus far. Nor do I pretend to have any idea of what the impact of their names will have on their future.

Will Triumph become triumphant? Over what? Poverty? Ill health? Will he achieve fame? A good job? A job? Will Resolve be resolute? Stick to his goal, like the Cowardly Lion, until he achieves it? Will Gentility learn to be solicitous of others? It seemed to me that she’d already begun acquiring the quality of sweetness, surely a component of gentility.

But how the naming will define them, I have no way of knowing.

What I can be fairly certain of, however, is what that mother had in mind. Fairly certain of the kind of human beings she wanted her children to fashion themselves into. And she was going to give them as much of a leg up as she could.

Note: Background information on the meaning of names throughout history was found in online excerpts from the book, The Hidden Truth of Your Name. Ironically, there was no author’s name attached. Only: “by The Nomenology Project.”

Thinking Outside the Box

Fantastical Animal Photo

What a Nifty Wagon!

IN AN EARLIER BLOG POST (What’s in a Name?) I wrote about three children called Triumph, Gentility, and Resolve (not their real names), As I said then, these children are from a low-income area of Toronto and come to school with limited verbal skills. They don’t get to attend the kind of enriching cultural experiences that broaden our knowledge and enhance communication skills, music and theatre performances for instance, that many of us take for granted.But they seem to have healthy imaginations. Unhappily, those young imaginations, needing so to be fostered, frequently don’t get sufficient opportunities to thrive, if even recognized as a potential. One Saturday morning, at the same enrichment activity program I spoke about in the earlier blog, they were given such an opportunity and they made the most of it.

My two colleagues had planned an unstructured box activity. Boxes of all sizes and materials were piled helter-skelter on the gymnasium floor: cardboard packing boxes; corrugated boxes. Boxes for a variety of uses: egg cartons, plastic food-storage containers. Assorted miscellaneous items: toilet paper and paper-towel rolls, tin cupcake or tart cups, wire, paper clips, string, tape, coloured markers, scissors. The only instructions given were to have an idea of what they wanted to make and to plan ahead before starting. They were expected to present their finished project to the group and explain how they went about constructing it.

When I first looked upon the scattered pile of boxes I couldn’t imagine what could result. I must have done similar, if not the same, activity as part of the kindergarten program I ran way back when, but I confess I have forgotten what the children had come up with or what the many possibilities might be. Much to my delight, they saw what I’d been unable to. Each small group came up with a different idea. Perhaps the slowest learner came up with the most unique concept and story. They all worked together in their units with cooperation and focus. Here’s what they came up with:

For Ants There’s No Place Like Home

Can You See Me On TV?

FANTASTICAL ANIMAL FOREST: A diorama. A tiger and duck standing in a surround of grass, sky, birds, trees, hills, and even a nest of honey for bears. Magic Markers, tape, scissors and a child’s imagination and skill were all that was used.

WHAT A NIFTY WAGON! Just big enough for a small child. Two wagon cars, connected by heavy string, with a handle fashioned also from string, and a paper towel cylinder, is pulled along by a friend. Wheels of very small boxes or toilet paper rolls are affixed under the wagon (cannot be seen in this image).

FOR ANTS THERE IS NO PLACE LIKE HOME: This child imagined quite a creative story of ant life! Inside the box, to the left, is a plastic food container for a bed. A yellow Oxo box (rear) makes for a fine TV; tiny tin cups become plates for holding food, and a tin cup turned upside-down serves as a chair for resting after the ants hard labour. Box flaps close for privacy. Another plastic food container, to protect against intruders, sits on top of the box, covering the ant hole in the ground, leading to the nest.

CAN YOU SEE ME ON TV? Fashioned from just a box and a half, held together with strong tape, this TV is made for viewing. An actor appears through the TV “screen”. This TV has a wire antenna (can’t be seen in this photo) and even a knob for changing channels.

I wonder if these children had ever had the advantage of LEGO sets?

Splendiferous!

Marion Filar, Pianist, Teacher

I knew much about the life of Marian Filar: his book, From Buchenwald to Carnegie Hall , (co-written Charles Patterson) told of his happy childhood and adolescence in a middle-class Jewish family in pre-war Warsaw; of his debût performance as a wunderkind with the Warsaw Philharmonic at age 5 and again at age 12; his acceptance into the Warsaw Conservatory and predictions of a brilliant career. And then . . . the German invasion of Poland; the Nazi murder of his mother, father, sister, a brother and his wife and their 3-year-old child; the deportation to Siberia of two brothers and a sister-in law by the Russians; and his subsequent struggle to survive Buchenwald and Majdanek.

When Mr. Filar came to the United States and was appointed Head of the piano department at The Settlement School of Music in Philadelphia, I was the lucky recipient of a scholarship given by the school and of another personal one from Filar himself. In all the years I studied with him and subsequent years, I heard him speak very little about the Holocaust. I knew only that much of his family had perished and that he survived the camps. I never saw bitterness, defeat, despondency or negativity. Some protection of privacy, yes; some indications of distrust of strangers, yes. Mostly, what I did see was a great warmth and commitment to his students, a deep love of music and a need to express that love through the performance of it. That expression channelled to the rest of us his human-ness, compassion, sensitivity.

After the war, still intent on a career as a concert artist, he found his way to the home of the famed Walter Gieseking, incomparable interpreter of Claude Debussy. After becoming convinced that rumours of Gieseking’s collaboration with the Nazis was untrue, and upon the maestro’s agreeing to accept Filar as a student, he (Filar) remained as Gieseking’s protégé for the next five years.

Filar first broke his silence when researchers for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation persuaded him to grant an interview, the tapes of which are housed at the Yale University Library. It was there, listening to him, that I first learned of the horrors of his Holocaust years. It was there, watching that tape, that I witnessed what at one time would have been unthinkable to me: a tearful breakdown of this man who had always carried an aura of centredness and strength. It was from that time on, the intentional allowing of a crack in the dam, that he was unable to stop the ensuing flood of words — almost a compulsion to tell the story.

When I last saw him in 2011, in a Philadelphia “retirement” home, a hotel-like residence with several levels of care, he was suffering from Altzheimer’s. He had his beautiful Steinway in what was two joined apartments, surrounded by framed pictures of himself with Walter Gieseking, Eugene Ormandy, Artur Rubinstein, and many other greats. Except for still intact memories about music, his playing, Gieseking, the past was largely gone. When he couldn’t remember an incident, a name, a place, he simply referred the listener to his book.

About a month ago, wondering how my marvellous piano teacher of many years back (the 1950s) was getting along since I’d last seen him, I called his place of residence to speak to someone there who could tell me. As soon as the person at the desk, and someone in charge of “events,” told me that there was no record of him, I knew immediately that he must have died.

Unable to break through the wall of privacy protection (!) I encountered, I went to Google where I typed in his name, Marion Filar, and to my surprise found a wealth of postings, not only about his passing, but about his life and career. To my delight, I found many from reporters who had interviewed him; from his students; and accolades by critics of his playing with major orchestras around the U.S. and the world (Philadelphia Orch/Ormandy, 5 times; Berlin State Opera Orch; Chicago Symph/Kubelik; Israeli Philharmonic, and many many more). Patricia Parr, a Canadian pianist and friend, led me to an old Colosseum recording on YouTube of him playing Szymanowski. I even found a priceless video — the last images of Filar before his death — taken by Charles Birnbaum, a former student.

How is it, you may ask, that this acclaimed musician never came to be one of la crème de la crème recognized by the music-loving public? One might say it was life itself, over so much of which we have little control.

For Filar, the war had interrupted his path, but more to the point, not understanding the fundamental difference between the arts/entertainment ethos of Europe and that of the United States, with its ego-driven competitive world of impresarios — managers, agents, recording producers — impacted heavily on heights of recognition he might have achieved. An inability to speak English when he arrived in his thirties in North America, could not have helped. The luck, fate, miracles, and his own wit and grit, that helped him manoeuvre his way through the treacherous years in Germany and Poland, failed him when he was faced with the New World free-market Culture industry. A loss to many, but for those of us who knew of his artistry, we have been rewarded and enriched.

In answer to how he found the strength to get through the Holocaust, Filar said it was the music in his soul, the overwhelming need to make music. His last statement to the Shoah Foundation interviewer was that the world should know that if it weren’t for the many “righteous” Christians (Poles and Germans) in Warsaw and Nazi-hating camp guards who covertly slipped him food or helped him escape conditions that would have meant certain death, he couldn’t have survived.

Filar is truly an inspiration. Splendiforous. Take a few moments to follow the links and see reviews below to find out for yourself.

1. Marian Filar Plays Szymanowski Four Preludes, Op. 1:

2. Marian Filar Plays Szymanowski Etude Op.4 No. 3:

(This story concludes in the post following and is part of the story of another amazing human being and musician. Please scroll down the Blog page.)

********************************************************************************

From the online Chestnut Hill Local, July 18, 2012: Legendary Pianist, Teacher . . . (by Len Lear):

“Filar was a powerful and personal artist of enormous integrity. I’m held in awe of this modest, giving man who possessed fingers of gold and a heart filled with hope and faith in the ultimate goodness of mankind. . . . Gieseking thought Filar and Rubinstein the two greatest living interpreters of Chopin’s music.

“In addition to his teaching, Filar distinguished himself as a world-renowned piano soloist with major orchestras (the Philadelphia Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra and many others) although he never received the recognition from the general public that he deserved. The accolades by critics for Filar’s virtuoso performances could easily fill up several articles the length of this one. Here is just a tiny sampling”:

•The Aftenbladet, a newspaper in Copenhagen, Denmark: “Marian Filar must be counted as one of the greatest living Chopin interpreters, maybe THE greatest!”

•The New York Times: “Filar’s incomparable technical facility is at the service of his utterly elegant musicianship. His performances are fleet, supple and beautifully nuanced … and just another indicator that exceptional talent does not guarantee wide public recognition in the often unjust world of classical music.”

•Arbeiterzeitung, a newspaper in Vienna: “A heavenly, rare, radiant piano hour … Filar belongs without doubt to the most fascinating pianists we have ever heard.”

•New York Post: “Filar’s playing recalls that of the late Josef Lhevinne, which I think is one of the highest compliments it is possible to pay any performer.”

Lives in Tune

a continuation of Splendiferous (see above Blog)

In his nineties, unmarried, and without children, Filar’s health was overtaken by Altzheimers. Charlie Birnbaum and another former student, Rollin Wilber, took over the job of caregivers, such was their gratitude for what Mr. Filar had given them as a teacher and friend.

Filar deteriorated into anger and aggressiveness, and, wanting desperately to see him made more content, Charlie and Rollin moved him back into his former apartment(!), where he had once lived a productive life of artist and teacher. They ensured he had his treasured Steinway with him, his framed photos; clues to lost memories. They encouraged him to place his fingers on the piano keyboard, his foot on the damper pedal, hoping that would help the maestro kinetically recall what his now-arthritic fingers could once manage with such virtuousity.

Young Charlie Birnbaum

This is where my search to discover more of Filar’s story widened and deepened, thanks to the “information age” and an interconnectedness made possible by modern-day technology miracles, search-engines such as Google and You-Tube. Looking for accounts of Marion Filar and his music, I came across a link to an interview with Mr. Birnbaum, where a whole new vista of insight, empathy and admiration opened, like looking through binoculars to bring into focus a wide expanse of distant fields.

Charlie Birnbaum at the Piano

Here’s the kicker: Birnbaum himself was once touted as on the road to becoming a great concert pianist. At the time of this writing, he had for many years been working as a piano tuner, at one time tuning the instruments for star entertainers at Las Vegas (the Rat Pack among them). So extraordinary was his playing, that when Charlie finished tuning the instrument and, testing its accuracy, took to playing one of the great works of music, a Beethoven sonata, a Chopin ballade, or a Mozart concerto, everyone waiting backstage would stop to listen in wonder. How did Charlie come to being satisfied simply to tune pianos? they wanted to know.

As with his teacher, Filar, life got in the way. Born in a displaced-persons camp near Neu-Ulm in Germany, a child of Holocaust survivors, Birnbaum has his own astonishing story of despair and triumph. What he has survived, the tragedies he has overcome, would defeat the strongest among us. Both he and Filar not only survived and overcame, but rose above.

Though saddened by life events, Charlie chose to build on his love of music; he chose to devote himself to “keeping his family intact,” rather than turn to defeat. He chose to care for his teacher and mentor, Marian Filar, magnificent interpreter of Chopin.

Birnbaum, Wilber and Filar

At some point, Birnbaum made a conscious decision not to continue striving to meet the demands of the concert stage. After a life of calamities and heartbreaks that would have brought down Job, in an interview article online at philly.com, by Inquirer staff reporter Michael Vitez, A Life in Tune: His hands still touch the face of God: Birnbaum is able to say: “You have to find a way to find joy in life. I don’t care if it means sweeping the sidewalk. What I’ve learned through my process is that I won’t trade my little successes that I have every day for one grand success.”

I leave you to discover for yourself the amazing story of Charles Birnbaum, who, like Marian Filar, is a rare “splendiferous” being. Please follow the links I’ve given below. “A Life in Tune” is a must-read. You won’t regret it.

1. A Life in Tune: . . . The Face of God:

http://www.philly.com/philly/news/124867814.html?c=r

2. Aging Prof’s Students Help:

http://articles.philly.com/2011-07-07/news/29747237_1_music-professor-nazi-camps-settlement-music-school

3. Marian Filar, Piano Teacher:

http://www.philly.com/philly/video/BC1041268807001.html

The Lady Who Spoke with a Yiddish Accent

Louis & Anna Rabinowitz

I loved my grandmother Rabinowitz hugely. In her sixties, which “back then” was considered to be quite elderly, Anna travelled cross the country by bus from California to the East coast to visit her sons and grand-children. She brought me and my sister turquoise jewelry, which we thought to be very exotic, from Indian reservations in the desert as she travelled cross-country. At night, sharing my bed with me, she’d “kitzel” my back, meaning she’d very lightly stroke it with her fingernails, and tell me stories she’d learned “first-hand” about Hollywood movie stars, like Cornell Wilde and Ava Gardner, which I know she made up to satisfy my imagination. My mother wasn’t so crazy about my grandmother, but I adored her.

Thinking she was doing the right thing, I’m sure, she broke up a love affair between her youngest son, my Uncle Louie, and an upstairs tenant, which broke his heart. He’d gone out to Los Angeles to find work and send for the woman he wanted to marry. After she called off the affair, at the behest of my grandmother, he decided to remain there and start a new life. But again, thinking she was being a good mother, my grandmother decided her youngest son, unmarried and “on his own,” with no family, sold her house in Philadelphia and went out to join him.

Anna Rabinowitz at Louie’s Taco Stand, CA

I don’t think he was too pleased, but being a good son, he welcomed her; he bought a Taco franchise and they shared a home together. Soon after, Louis met another young woman from Poland, Doris Springer, a survivor of three years in a concentration camp during the Holocaust. Amazingly she and 6 members of her family survived. Hers is quite a story.

My grandmom didn’t approve of Louie’s new wife because she “spoke with a Yiddish accent.” I remember, somewhat ironically, that during my grandmother’s visits East, she would speak to my father in Yiddish, which, again, to me was wondrous. To this day, I see her standing in our tiny kitchen, speaking what to me was an exotic language and my father answering her in kind. Of course, the Yiddish was interspersed with English, no doubt for my mother’s benefit, and it was during those conversations that I came to understand my grandmother’s displeasure with Doris. You see, Anna, at age sixty-five, had gone to school to learn how to speak, read and write English more fluently and she couldn’t understand why Doris, a much younger woman, couldn’t do the same.

Although my grandmother and her sons (my father Morris, Sammy and Jacob; Louie was born in the U.S.) had run from the pogroms of Czar Nichalas II of Russia, I suppose she didn’t really understand how traumatized this young woman must have been, coming so recently out of the Holocaust.

When Doris and Louie’s son, Allen, was two-and-a half, Anna decided she had cancer and went for an exploratory operation. She was clear of cancer, but she did have tachycardia (heart palpitations) and, being in her seventies, was unable to withstand the stress of the surgery; she died on the operating table. Louie wasn’t happy about losing his mother, but he did tell his brothers he was at last “free.”

Sadly, a doctor had been treating Lou for indigestion, when in fact he had colon cancer. By the time he was properly diagnosed, it was too late and eight months after Anna died, he passed away, after having suffered a painful dying. He left Doris to raise young Allen, who had been born with a rare affliction, which Doris conjectured came from a genetic mutation as a consequence of her being forced to work with poisonous chemicals in the concentration camp munitions factory. Doris herself was still suffering from what today would be called post traumatic stress.

Doris (Springer) Rabinowitz (Rabin)

As you will know, if you have read the previous post (see below) to this Blog, Doris and Allen only recently re-established contact with Louie’s brothers’ families, after decades of searching. And only recently have I learned what a brave, resourceful, smart woman my Uncle Louie married. The woman that my grandmother disapproved of because of her lack of English fluency, her Yiddish accent, her “Old World” ways, has written an e-book on Kindle, called “Kiss Every Step.” Under the name of Doris Martin, co-written with her husband (she remarried some years after Louie’s death), she tells of her and her family’s struggle to survive.

I have long known of the horrors of the Holocaust. Like all Jews that I know with similar stories, I have relatives who perished. I have read extensively on those awful times, and I have written stories of them. But Doris’s account is so very personal, so vivid, so descriptive and painful, that I am filled anew with the unfathomable bestiality and sadism of the Naziis.

Not only did Doris survive, but she survived to tell her story, in a language not her own, and beyond that, has gone on to speak publicly about those experiences, bringing her message to young and old so they won’t forget.

Some people are what I call “Splendiferous.”

High Tech to Highly Personal

Patriarch and Matriarch,

Benjamin and Anna Rabinowitz

“Please contact me. I think I am your cousin. . . . I have been searching for my father’s side of the family for decades. . . . Hoping to find out about my paternal family.”

This is the message I received by way of a comment left on the Moon Over Mandalay page of my website. The name given as the commenter was that of someone I thought I’d never locate and whom I’d never met.

Immediately, I called the number left in the comment headings. The voice that answered seemed hesitant and my first thought was that this was going to be a very awkward conversation. It turned out to be anything but. When he heard who I was, there was an audible silence, then a catch to the voice, saying he needed a moment to get hold of himself. To my amazement, he broke down and cried, so moved was he by making contact with a member of the family he’d been trying to find for so many years.

Louis & Doris (Springer)

Rabinowitz (Rabin)

Living in California, away from his father’s relatives in Philadlephia and New Jersey, Allen was only two-and-a half-years old when his father, my uncle Louie, died, and never really knew his father or his uncles: Morris, Sammy, Jacob; all but Morris changed their names to Rabin). Louie married a woman, Doris Springer, who was a survivor of three years in a concentration camp during the Holocaust. Miraculously, all seven members of her family survived. At some point, after several moves, and having lost contact information for the Rabinowitz side of Louie’s family (my father Morris, brothers Sammy, Jacob, and their families), they fell out of touch. As for us, the Eastern seaboard Rabinowitzes, we had no idea where she and Allen had moved.

The route to discovery could only have come about in today’s world of technology and its search engines, Google, Ancestry.com; internet notices of events, such as the obit mentioned below); and my Website. Posts on Ancestry by an unknown woman (“Joey”) searching for long “lost” cousins, and data posted by another stranger simply interested in searching ancestries, led Allen to an obituary, which mentioned me, “Rhoda Green,” as a surviving daughter. That led Allen to my Website, where I use the writing moniker of Rabinowitz Green. With no contact information given, he left a message in the Comment section of my novel, Moon Over Mandalay. Great sleuthing!

“Joey” — simultaneously but independently looking for cousins with the same names Allen was searching for — turned out to be Sam Rabinowitz’s granddaughter. Through a falling-out between his (Sam’s) children, brother and sister lost contact with one another and went their own ways. The result of this estrangement was that Joey knew almost nothing about her extended family or their whereabouts. And we had no clue as to where they had “disappeared.”

When the older generation died, a certain core was lost; an era had passed; children married and moved on.

I have wonderful recollections of my Uncle Lou and Uncle Sammy. They were both special in their own way. Louie was an albino, and that made him special in my eyes straight away. Like many albinos, he had very poor vision. He was kind and gentle and soft-spoken. Sammy was a fine artist, though he worked as a shoesalesman, and for many years I coveted two mosaics he had done, made from cracked eggshells and painted, scenes in brilliant colours of Humpty Dumpty sitting on a wall, and of the Royal Court of England.

There must have been a gnawing feeling of incompleteness — a story left unfinished — that drove Allen and Joey to search over decades until that quest for those who’d peopled their parents’ past (and therefore their own) was successful. Though married (his wife suffers from several illnesses and is largely bed-ridden), being an only child, with no children of his own, and never having known his father, I imagine he lived a large part of his life with an aching feeling of aloneness. Hopefully, some of those feelings of isolation, for both Allen and Joey, will be calmed. Morris’s daughters, Rhoda and Bonnie, being older than Allen and Joey, have vivid memories to share, as well as photographs of family so long gone.

Like rays of light, each communication amongst us illuminates what had been a void, and, broadening outward, expands what we know, not only about each other, but about ourselves. The discoveries provide a context into which to place our lives. I think this need must be universal.

From a personal point of view, reuniting has enriched my life. It has led to discovering remarkable stories. But those are for another time.

What Would Helen Say?

If I tell you, how will you know?

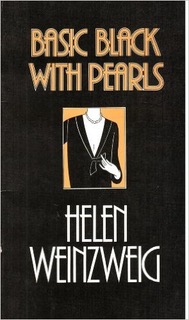

Basic Black with Pearls

The above quote, taken from Zen Buddhism, is just one of the many wise maxims passed down to me by Governor General’s Award Winning author Helen Weinzweig (Basic Black with Pearls; Passing Ceremony). I met Helen in the early 1990s, when I was in my fifties and she in her late seventies, looking at eighty. At the time, she was working on a new novel.

Her raison d’être for writing never came with an eye toward publishing, but from a compelling intellectual curiosity and a need to explore life, experience and new approaches to form. That she was in the dusk of her life — though she lived to 95 — was not something that disturbed her, other than to make a point of conserving for her novel her dwindling energy. She once said to me, “I love old age. Every time I looked at life throughout the years, I found nothing there. Now, suddenly, it is what it is and nothing else. Old age has released me.” No more striving, competing, struggling to prove herself. She could simply be and do (write), and therein lay the intrinsic value, simply the process of living and toward no other end. At another time she commented: “Maybe if you discover the past in your writing, you’ll discover the past in your life. We write to understand, to work out the unresolved issues of our childhood.” And finally, perhaps her most profound statement on growing older: “Aging,” she said, “is the downward path to Wisdom.” You can understand why I considered Helen to be such a valued friend and mentor.

I came to meet Helen by way of a reference from a mutual friend. At the time, a trained classical pianist and new to the country and writing scene, I was seeking constructive criticism of my work and advice on publishing when my friend suggested I meet Helen, with whom I would share interests in both music and literature.

That led me to the most open, generous, smart, talented woman, with the most liberal and unique mind, I will ever meet. So sensitive was she about the challenge of “breaking into” an established community of artists, both as a musician and writer, that she called the very next day. “I know how anxious-making it is to wait for a response and wanted you to know that I’ve already begun to read your stories,” she said. “Artists tend to be protective of their own turf, it’s a competitive field.” She was keen to counter that attitude, keen to “give back,” to pass on a legacy. She offered some complimentary words and offered to work with me. That was Helen.

Helen had a unique ability to examine a story and go laser-like to the heart of what was working, what not, and why. “All the “stuff” of a good writer is right here,” she said, referring to my manuscripts. “But something is keeping these stories from being published.” And then she began, analyzing one script after the other. “So what’s the hochma (hockma)? she’d put to me. Because of the context in which she used the word, I deduced her meaning. An internet website, Abarim Publications, tells us that the word is the Hebrew version of the name Sophia, meaning Wisdom and that the Biblical concept of wisdom is much broader than our modern understanding of it; in order to determine what’s wise and what’s not, one would have to know what wisdom wants to achieve. The Abrahim Theological Dictionary says that not only does the quest for wisdom mark the old world literature but also its definition. Wisdom to the later Greeks was said to come from intellect and speculation; to the Hebrews it meant skill in practical matters, based on divine causes. It was not, then, theoretical and speculative, but practical, based on revealed principles of right and wrong.

Helen’s question, So what’s the hochma? forced me to determine, in one revealing sentence (or several should they be related) embedded in the story, what the story was about. Its essence; its wisdom, around which everything in the story must relate, or be seen as relevant. Not that the writing should be so rigid as to never deviate, fleshing out a character, an aside of humour, a brief memory, but not for long and always making its way back to the hochma. Amazing how the application of that one question can focus the writing, how much extraneous material can get discarded, giving shape and a through-line to the narrative

Helen was a master at moving effortlessly between past and present. Her observation: “In the unconsciousness, Time repeats itself,” though profound, its meaning is nevertheless somewhat abstruse. Yet, I believe it speaks to the notion of the seamless blurring of time shifts found in her text: “Use memory as if still a fact of the present. Look for phrases that take the mind back, not the event. Keep the event in the present; don’t break the narrative thrust.”

Her novel, Basic Black with Pearls, is replete with such instances. Shirley Kazenbowski, néeSilverberg, is a middle-aged, middle-class woman who throughout the novel wears a basic black dress and strand of pearls. Walking the streets of Toronto, she searches for her lover Coenraad, who is always in disguise and a mysterious member of “The Agency.” Coded messages in the National Geographic leave clues as to where he will rendezvous with Shirley. She is led to a house on Elm Street where she wanders the corridors of the tenement and hears the various sounds coming from the apartments:

(Italics and [ ] are mine.)

“The television voice was clicked off in mid-sentence. . . . For several moments I stood there in the dark and breathed in the smells of the poor, thinking that Coenraad, were he with me, would take my hand and pull me out of this place, exactly as he did that time [we’ve slipped into time past] when our rendezvous turned out to be a hovel of a hotel in Manchester. He has [present tense] an aversion, which I do not share, to poverty. Coenraad refuses to reveal whether, like me, he once was very poor. . . I agree that in his line of work . . . he needs to be able to count on something. He can count on me . . . And yet . . . I am always drawn back to poverty. I am aware that there are [present tense and time] a dozen streets named Elm, in the suburbs, in Rosedale, in North York, still, on my first day back, I sought [past tense] the shabby streets of my youth [continues in past tense to the end of the passage but in present time). Suddenly what I thought was self-evident in the message now appeared vague and uncertain: did I really expect to find Coenraad here?”

Helen brilliantly keeps us feeling that we are in the present, even when her narrative takes us to a past memory. Even choice of phrases, such as “the smells of the poor,” “an aversion to poverty,” “once was very poor,” and “drawn back to poverty,” work as transitions between the past and present; in this case, the words “poor” and “poverty” serve as connecting doors opening to the before and now.

Because of the restrictions of length for a blog, I’ve given but one example. Should you be interested, you will find the entire Basic Black with Pearls, a work of memory in itself, to be a source of impeccable technique as it takes us into the mind and emotions of Shirley Silverberg Kuzenbowski, keeping us always in a present past.

I owe much to Helen Weinzweig and want to share part of her legacy with you. More on “What Would Helen Say?” and her use of Magic Realism to follow in a coming blog.

Rhoda Rabinowitz Green

Author, Aspects of Nature

Inanna Publications

Please go to <inanna.ca>

Helen Weinzweig: From Pain to Prose

Helen Weinzweig

I. “What Would Helen Say?” (Inanna, Januarty 6, 2016)

II.”From Pain to Prose’” (Inanna, March [date] 2016

Helen Weinzweig is the author of Passing Ceremony and Basic Black with Pearls, winner of the Toronto Book Award. Her short story collection, A View from the Roof, was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction. Helen Weinzweig died in Toronto in 2010.

My interest in Helen Weinzweig and her work was renewed with the recent republication of her second novel, Basic Black with Pearls (Anansi). Trying to remember what Helen had said about writing back in the early 1990s when she’d agreed to mentor me, coupled with the desire to satisfy my curiosity, led me to search through my file notes, where I came across invaluable words of advice she’d offered. What I found in those notes impelled me to write “What Would Helen Say?” posted in January 2016 on Inanna’s Blog. I found in researching the piece that there was so much to her life and work I couldn’t possibly include it all in one posting and determined to follow it up with another, expanding on the first.

Not surprisingly, after writing several drafts of “From Pain to Prose,” I again determined there was too much material to be absorbed in one reading. This segment, then, will speak to the traumatic experiences of her childhood, her growing awareness of thwarted self-fulfilment and her search for identity, and how they are revealed in her writing. Because of the close relationship between her life experiences and the style she chose to best express them, the sequel to this blog entry will deal with how she used magic realism to that end.

Given what we know of her life, career and personal relationships, we can’t help but read an autobiographical truth into Helen’s novels and stories. Nor can we help but recognize the pain that imbues both her fiction and her life.

One of the most telling and intimate portraits of Helen can be found in Michael Posner’s Globe & Mail 2010 Obit: “Helen Weinzweig Turned Personal Pain into Beautiful Prose.” [The article contains quotes from an interview with Posner based on my personal/professional relationship with her.] As well, poet Ruth Panofsky, in a very full account, further tells of Weinzweig’s struggles through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood as student, wife, mother and eventually, writer (Panofsky, “Sense of Loss; A Profile,” The Atlantis, Vol. 22.1). More can be found in Stacey May Fowles’ “Special to the Globe and Mail,” 2015).

Helen grew up in the impoverished polish ghetto of Radom, Poland under constant threat of pogroms. She was the only child of a “tempestuous” marriage between the “. . . young, illiterate, fiercely independent [and] physically beautiful” Lily Wekselman and her father, the “brilliant Talmudic scholar turned atheist and anarchist,’ Joseph Tennenbaum. The marriage did not last.” Helen arrived in Canada (with her then-divorced mother), aged 9 and illiterate. She never understood why she hadn’t learned to read or write but conjectured that after being expelled for stealing a book she never returned to school. Was that because of shame or because her mother couldn’t afford to (or wouldn’t) buy the schoolbooks? She didn’t know. (Posner)

“Scene: “My Mother’s Luck,” Foxborough stage production A VIEW FROM THE ROOF (Dave Carley), Based on Helen Weinzweig’s story collection of the same name

Weinzweig grew up in Toronto’s Jewish immigrant district, now the gentrified “Annex.” Her life-long obsession to escape the “tyranny of poverty” and “working-class oppression” (Panofsky) provides the backstory for a long monologue, “My Mother’s Luck,” (A View from the Roof), acknowledged as autobiographical. Helen’s mother earned a scant living in Toronto as a hairdresser and “welcomed a parade of unsuitable men into their lives, some [three] as husbands, others as transient lovers,” resulting in a number of abortions. (Posner) Because of being shut out of the house while her mother “entertained,” Helen wandered the neighbourhood, house-to-house, street-to-street, the brunt of ostracism because of her mother’s life style. Yet, in “My Mother’s Luck,” she sympathetically explains her emotionally abusive mother’s behaviour as stemming from the need to be sole provider for Helen, Helen’s sisters and grandfather, at a time when such a role was not normally required of women. Fortunately, she found refuge at the St. George’s Children’s Library. There, librarian Sadie Bush nurtured her with treats of biscuits and books, instilling in Helen a love of reading and language. (Posner) The theme of poverty runs through the whole of her work.

Later in life, her difficult adolescence became grist for her writing mill. At 17, thinking to have a reunion with her long-estranged father in Milan, she found herself essentially a captive for months, “kidnapped” by a father who refused to allow her to leave. On returning to Toronto, she contracted tuberculosis. During the next two years in Gravenhurst, a sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis, and motivated by a keen intellectual curiosity, she educated herself in world religion and Western literature.(Posner) She soon came to the realization that all the books she was reading were male authored —written from the male perspective. It was the male “voice’ she was hearing; the women’s voice was silent; unacknowledged. “One of the things I had to learn . . . was, what do I as a woman feel like,” she has said. “All the literary forms . . . all the philosophies were men’s . . . The hardest part . . . was learning to use the first person singular. It was then that I was shocked into admitting that I rarely said “I” except in apology . . .” (Weinzweig, “The Interrupted Sex,” quoted in Panofsky and Fowles)

Forced by the economic consequences of the Depression, she left high school at the end of her junior year at Harbord Collegiate. A chance meeting on the street of high school friend, John Weinzweig, led eventually to their marriage. Her son, Paul, has been quoted as saying: “The only immediate problem was that [my mother] came from the wrong side of the streetcar tracks. She had an uphill battle to convince the Jewish bourgeoisie that she was legit.” (Posner) Explaining her decision to marry, she said: “I grew up without a sense of family . . . I tried to create a family life out of my head. I feel I failed. I still don’t know . . . what makes a family. So the “sense” of family creeps into my work in a negative way . . . My mother] refused to follow the path of other women . . . [So] I decided I would be respectable, and became more so than Caesar’s wife. (Jenoff, “Helen Weinzweig: “Her Life and Work. An Interview,” Waves 1985; quoted in Panofsky).

Speaking about her novel Basic Black with Pearls, Helen said in an interview: “[The novel] reflects my desire to belong to [a] bourgeois, nuclear family. The inherent conflict was to want it and to despise it.” (Panofsky, ‘At Odds in the World,” Essays on Jewish Canadian Women Writers, Ryerson, 2008; quoted in Posner). She devoted herself until age 45 to being a homemaker and mother, volunteering, as many women do while raising their children. Helen was quoted in 1976, after publication of her first novel, Passing Ceremony (1973), as saying, “Both John and I lived for his career [italics mine].” (Keeler, National Post, Basic Black with Pearls Review; 2015) In my own catalogue of memories of conversations with Helen Weinzweig, one revelation, delivered with poignant dismay, has never left me: “John never reads my work.”

There has been much written on the success and fame of her composer husband John Weinzweig. It is John who is referred to as “revered, who wrote compositions for film, radio, theatre, orchestra, chamber groups, solo instruments, choruses. John, professor at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music, Officer of the Order of Canada. He who is presented with awards and testimonials; who establishes (with others) the Canadian League of Composers and writes extensively on music and composing. His bio is extensive, his output prolific.

As for Helen, she published two novels and a number of stories: Basic Black with Pearls won the City of Toronto Book Award; A View from the Roof, a collection of 13, was nominated for the Governor General’s Award. Passing Ceremony broke new ground in Canada as a highly experimental work in the best tradition of avant-garde writers. She was a founding member of the Writers’ Union of Canada, held positions as Playwright and as Writer-in-Residence at Tarragon Theatre and University of New Brunswick, respectively. In her approach to reaching a final draft, she was meticulous, constantly rewriting. That, along with the fact of having begun to write relatively late in life, led Anansi’s Editor James Polk to comment: “A painstaking artist, she . . . produced relatively little. But what there was, was choice.” (quoted in Posner)

But it was John who was highly prolific, held positions in many high profile capacities and was extensively written about. In short, it was John who was famous.

With her two sons growing up and away, and her husband engrossed in himself and his career, she met with a Toronto psychologist Margaret McQuaid. Helen was in her mid-forties. One day the psychologist suggested to Helen that she put her thoughts and feelings to paper in just the way she’d been describing them. Helen took her up on it and so began her exploration of the many unresolved issues from her traumatic childhood and adolescence, as well as her role as a woman in a male dominant society and marriage. Helen says the writing gave her renewed life.

It wasn’t until her sixties that she began writing Basic Black with Pearls, at a time when she was seeking “a female-gendered narrative form that would articulate the feelings of depersonalization and fragmentation that women, particularly of her generation, experience.” (Panofsky) The book’s protagonist Shirley’s narrative becomes a personal transference of Helen’s deeply felt pain arising out of her own experience, that of prevailing personal and societal male control, determining her destiny and options, placing limits on her potential. (Fowles, Globe and Mail, August 2015).

On first bringing my own work to Helen, seeking her critical insights, Helen observed: “All the stuff — the substance — necessary for good writing is already here in your manuscripts, but something is keeping them from getting published.” She then proceeded to work with me on finding the form and style to best support and reveal each story’s emotional meaning. For Helen, it was magic realism that provided the means for expressing that which would otherwise be inexpressible, allowed her to slip seamlessly in and out of reality. In Basic Black with Pearls, it is magic realism that allows her to express her pain through Shirley’s consciousness. And it is magic realism that allows us to share that pain, felt as immediate and acute throughout the body of her work. It is her use of magic realism that will be the theme of a subsequent blog.

Rhoda Rabinowitz Green

Inanna author

Aspects of Nature, May 2016

Please go to <inanna.ca>

Helen Weinzweig and Magic Realism

My most important problem was destroying

the lines of demarcation that separates what

seems real from what seems fantastic.

Gabriel García Márquez

Helen Weinzweig

I. ”What Would Helen Say?” (Inanna, January 6, 2016)

II. “From Pain to Prose” (Inanna, March [date], 2016)

III “Helen Weinzweig and Magic Realism” (Inanna, March [date], 2016)

Helen Weinzweig is the author of the novels Passing Ceremony and Basic Black with Pearls, winner of the Toronto Book Award. Her short story collection, A View from the Roof, was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction. Helen Weinzweig died in Toronto in 2010.

“Helen Weinzweig and Magic Realism” follows “What Would Helen Say?” (Inanna Blog, January 2015) and “From Pain to Prose” (Inanna, March 2016). In the first, I wanted to pass along some of Helen’s insights on writing that I’d been the lucky recipient of; in the second, I tried to tell of her life experiences and the personal pain arising from some them, how they are revealed in her work. In this, “Helen Weinzweig and Magic Realism,” I have written about how she used magic realism to transport her feelings of trauma and pain into language the reader could emotionally grasp.

I believe it was the commonalities we shared that sparked the bond I felt with Helen when we first met in the early 1990s; perhaps it was the same recognition that engendered her willingness to foster the mentor-student relationship, even friendship, that grew between us. We both started writing late in life (her first published story came at age 52; mine at 58); both felt the consequences of 1950s attitudes towards women; both whose work was grounded in a Jewish sensibility. It was the recalled memories of that association and her teachings that led to my writing the first two blog pieces on Helen and her work, and now this, “Helen Weinzweig and Magic Realism,” the third and last.

Magic Realism is a term applied to a technique that combines “realism and the fantastic so that the marvelous seems to grow organically within the ordinary, blurring the distinction between them.” (Wendy Faris, in Magical Realism, Duke University press, 1995). The realistic and fantastic are seamlessly integrated, but when fantastic elements begin to enter the story of ordinary people living ordinary lives, neither narrator nor characters take any notice, mentioning them casually without further reference.

Magic realism can be a means of dealing with painful traumatic memories, [expressing] . . . “not what actually happened, but what was experienced as happening.” (Eugene Arva, The Traumatic Imagination Cambria Press, 2011). Pain itself cannot be expressed in language, but the “magic’ in magic realism (images produced in the imagination) can allow the writer/reader to translate what is unbearable into imagistic language, mimicking, or simulating, pain. Arva, a German scholar and professor of Engish, uses the term “traumatic” imagination to describe an “empathy-driven consciousness,” which converts pain into an emotionally understandable image that can then be expressed in language. Magic, i.e. the imagination, or traumatic imagination, therefore, is the “indispensable element” that allows for breaking through the paralysis caused by the original trauma to reach an understandable narrative, one the reader can emotionally intuit. (Arva, quoted in A Thesis on Magic Realism, Jo-Anne Sparrow).